Decarbonising New Zealand’s freight railway

This article is derived from a paper presented at the August 2025 Conference on Railway Excellence in Auckland. It summarises an internal KiwiRail study recommending electrification based on a mix of extending overhead line electrification (“OLE”) and battery electric locomotives as the preferred path to decarbonising the KiwiRail mainline locomotive fleet by 2050. The article focuses on the technical rather than the business aspects of the issue.

1. The basic problem (opportunity)

Rail transport emits less carbon than road transport per tonne kilometre now and likely will in the future. If rail can achieve a higher freight mode share, this alone will lower supply chain emissions for New Zealand and enable KiwiRail to contribute to the Government’s Emissions Reduction Plan freight target of a 35% reduction by 2035, even with the continued use of diesel locomotives.

But rail would still be creating some greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions. Rail’s full contribution can be achieved only by decarbonisation of its locomotives.

The evaluation of decarbonisation strategies integrated three significant analyses; the traffic levels to be carried in future, the potential technical choices on fuel and motive power, and the economic evaluation of these, in conjunction with a practical plan for delivery.

2. Traffic and train modelling

2.1 Traffic levels

Determining a locomotive decarbonisation strategy starts with future traffic levels. A very busy railway can justify decarbonisation using high fixed cost solutions like conventional OLE.

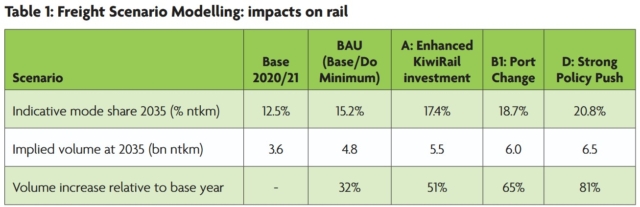

The Ministry of Transport Freight Futures model was adapted by KiwiRail to test rail’s ‘full potential’ under five supply chain scenarios . These represent different ways to configure NZ’s freight supply chain to achieve lower emissions and are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Freight Scenario Modelling: impacts on rail

2.2 Representative trains

KiwiRail’s new 3 MW/415 kN Stadler DM class was selected as the reference locomotive, as it represents the most capable and economical practical diesel-electric locomotive for New Zealand All the proposed locomotive options had to meet the same duty cycle as a DM hauled train and then be compared to the DM for economics and emissions.

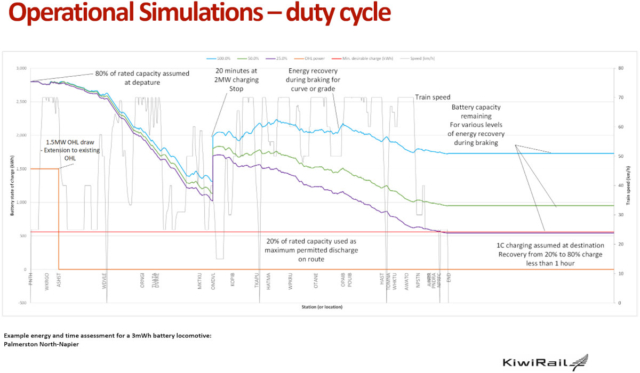

2.3 Operational simulation

Train operation was simulated using “Open Track” over fifteen operationally sensible route sections, outputting a wide range of performance parameters, including the energy used each second of the journey.

The results were also used to determine the parameters of the zero-GHG locomotives proposed to take over these duties; amount of on board energy storage required, per service energy supply demand and some infrastructure requirement e.g. fuel and energy storage and transmission infrastructure. This was an iterative process, particularly with the battery and hydrogen fuel cell locomotives, with early iterations falling short of the required performance in some criteria.

3. Energy sources

A series of facilitated discussions with suppliers was held to better understand different technologies, leading to combinations of fuel and motive power.

- Drop-in Biofuel (2nd Generation)

- Blended Diesel

- Green Hydrogen

- Electricity Battery locomotive

- Electricity Continuous / full overhead electrification

- Discontinuous / partial electrification

4. Technical feasibility

The short listed solutions were then analysed to arrive at a practical concept which could meet the DM duty cycle. This sometimes required significant change to the locomotive configuration to offset weaknesses and take advantage of strengths of that that particular power train and deliver a concept that could be substituted for the reference locomotive.

5. Conventional electrification

Electrification of the economy and decarbonisation of electrification underpin plans to achieve zero GHG and railways are one of the few transport modes for which electrification is long established and conventional technology.

The factor limiting OLE is the high capital cost of the fixed infrastructure required. In New Zealand the grid connection challenge is particularly high, also causing difficulties for battery locomotive charging.

The costs of electrifying at 25,000 volts AC were applied to the entire New Zealand network. As expected, at $8,298m the capital cost was considerable and the OLE option, when applied to all mainline freight routes, economically ranks as the worst performing of all the decarbonisation options.

Discontinuous electrification was also found to perform poorly in New Zealand conditions.

However, OLE can be more cost effective when the investment is filling gaps in an electrified route, including extending electrification to allow battery electric operation over the full length of a partly electrified route, so long as traffic levels are sufficient.

The Hamilton (Te Rapa) – Pukekohe and Hamilton – Tauranga (Mount Maunganui) routes are well used (just over 5 million gross tonnes p.a.) and would connect to the current Palmerston North – Hamilton electrification.

While only two routes, 46% of the entire KiwiRail freight task would be decarbonised by this initiative, using proven technology deliverable to a planned schedule. These two routes are where most of the traffic growth will occur, so this proportion will grow towards 60%. Selective electrification of these busy routes gives promising results.

6. Battery electric locomotives

6.1 Battery chemistry and control

Three commercial scale battery chemistry options were considered, in terms of their energy density, specific energy, power density, charge and discharge rates, and lifespan vs depth of discharge vs charging rates. Because multiple locomotives are required, the more robust but lower performing Lithium Ferro Phosphate chemistry is viable and was assumed. Nevertheless the supply industry will settle on the optimum battery for 2030 and onwards.

6.2 Battery locomotive configuration

The driving factor for battery locomotives relative to diesel-electric is the low energy density of batteries per unit weight compared to diesel fuel. Time to recharge compounds the impact of the resulting limited range. Within the constraints of the NZ network, the volume of batteries is not limiting, but the weight of a battery fit out is.

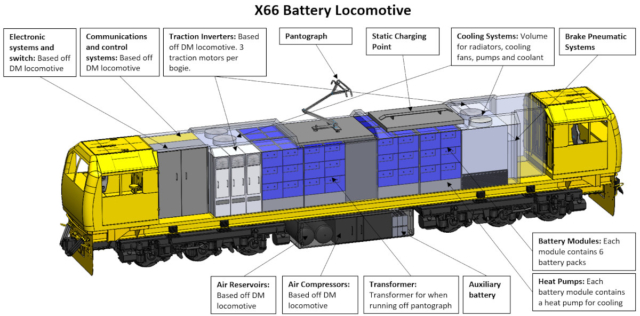

Two battery locomotive concepts were explored in depth, the “X-64” and X- 66”. The X-66 represents a simple conceptual “conversion” of the DM locomotive to battery power. That is a double cab, six driven axle locomotive of 3MW power with a gross weight of 108 tonnes. A six axle locomotive is conventional technology. The weight of the locomotive rolling chassis itself reduces possible battery capacity and the high power of the single unit exhausts this limited capacity quickly.

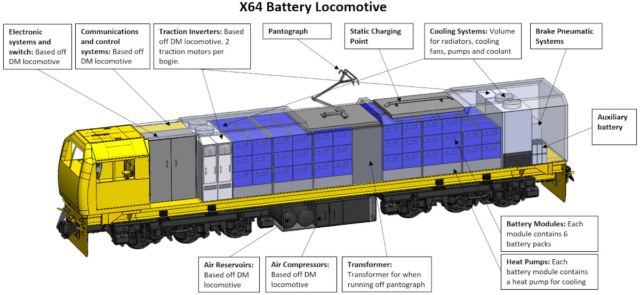

The hypothetical X-64 starts with the DM configuration and optimises it to maximise battery capacity by minimising locomotive weight within the 108 tonne limit. The end result is a shorter single-cab locomotive of 1.8 MW power, with only four of the six axles driven, to reduce the weight over other components and leave more of the 108 tonnes available for battery.

The operating concept is that two 108 tonne X-64 locomotives are used on the reference train, this combination allowing a very high battery capacity to be taken on the journey. A towed battery tender is often proposed and essentially two smaller locomotives are the tender concept stripped of its operational disadvantages.

The X-64 is the preferred configuration (in the model) at this stage, with the best ratio between tractive power and battery stored energy. From the mid to late 2030’s battery development is assumed to make the X-66 concept viable.

6.3 Charging

Currently, charging economically is the largest uncertainty surrounding the choice of battery-electric locomotives. This is a consequence of the sparse nature of the NZ electricity grid transmission and lines distribution network, the high-power demand of fast charging batteries of the size required for locomotives and this high demand being in rural and regional NZ.

All charging options depend on the available high voltage supply (the main Transpower transmission grid or, for most locations, the local lines company network). The power demands for rapid charging of two or four (ie, two pairs crossing) X-64 sized locomotives at a rate of 1C are equivalent to a town or a significant industrial facility. In many rural lines networks the basic network will not be able to supply the load at all. Significant upgrades will be required. This challenge could seriously undermine the viability of a battery based operation that depends on judicious enroute charging.

This study assumed that a national initiative would overcome these connection and supply difficulties.

Limited study of Energy Storage Systems, or large batteries, at charge points suggests this offers a way to make high rate locomotive charging viable in local-lines-only areas.

6.4 In motion charging

Initially, it was assumed that a battery locomotive could charge from OLE strung for a few tens of kilometres at the right places on a battery operated route: In-Motion Charging (IMC).

The need to install high capacity on-board chargers, technical capacity limits with standard pantographs when stationary and the particularly high cost of the power supplies for isolated OLE sections resulted in IMC being set aside in favour of static charging.

Where battery locomotive range extension by using OLE was beneficial, this was best achieved by extending existing OLE a distance up the unwired route. This delays the need to begin drawing down batteries, without a very expensive isolated OLE section and its standalone power supply.

The potential for battery swapping as a rapid alternative to charging was not considered in any detail. In the rail context, swapping locomotives enroute is the equivalent of road vehicle battery swapping.

With the time and capital cost of providing for static charging or OLE extensions, in some cases taking more batteries along, in the form of an additional locomotive, will be the best value solution.

7. Hydrogen

7.1 Hydrogen fuel cell locomotive

Fuel cells are the preferred energy conversion approach for using hydrogen in a locomotive. While there are early production road vehicles and some prototype passenger trains in demonstration service, hydrogen fuel cell locomotives exist only as a handful of prototypes.

Fuel cells are very simple in concept, but the practical execution of this concept results in a precision device requiring significant on board support equipment and clean operating conditions.

Hydrogen has a low energy density. Even at very high pressures or cryogenically liquified a large storage volume is required on board a locomotive if it is to be able to complete its required duty cycle – run from one terminal to another hauling a useful load.

It was not possible to package the required H2 storage, batteries and fuel cells on a locomotive of this size and performance and deliver a useful range. On essentially any route a DM sized locomotive would require mid route refueling. While not impossible, the cost, complexity and time delay of mid route H2 replenishment makes this option effectively impractical.

The result is to drive a solution similar to the battery locomotive, the required performance being spread over two locomotives that provide more total spare weight carrying capacity and volume per unit of performance than the single locomotive. The major difference from the battery case is that the limiting factor for batteries is weight, while for hydrogen weight and volume are both limiting.

Therefore, the recommended H2 fuel cell locomotive is a lower power single cab unit, used in pairs in the same way as the optimum battery locomotive.

7.2 Hydrogen fuelling

The hydrogen production network required to service the 2030 KiwiRail need has a capacity (demand) of 199 MW, similar to the network for road planned by Hiringa New Zealand.

High volume hydrogen refueling is surprisingly slow. Hiringa consultants recommend a dual dispenser for each locomotive to deliver a theoretical maximum rate of 864 kg/h. They estimate that a practical dual dispenser can fill an empty locomotive in 1 – 2 hours, Typically the refill is more in the range of 600kg, 45 minutes with a dual dispenser, 1 ½ hours with one.

7.3 Discussion

The battery locomotive uses the generated electricity directly, without the complex technology, energy losses and risks resulting from interposing an additional intermediate energy carrier (H2) between generation and locomotive wheels.

The combination of poor overall energy efficiency, complexity, maintenance requirements, the requirement for a battery in addition to the fuel cell equipment, development risk, and also requiring a pair of locomotives, mean that an H2 fuel cell locomotive compares poorly to a battery locomotive (also a pair) wherever the duty cycle is within the capability of a pure battery locomotive.

For these reasons hydrogen fuel cell locomotives (or range extender units) have been rated as a future fall-back option to 1) battery-electric locomotives and 2) biofuel, if required in the late 2030’s.

8. Liquid biofuel

8.1 Blended biofuel

The study simplified non-mineral fuel into two streams. Sustainable fuels that are blended with fossil diesel; and those that used pure (100%) biofuel.

While a locomotive can use blends of up to 20%, they can be problematic, and blended fuels are not considered in detail in this study. KiwiRail takes its diesel from the general supply and will be a blended product consumer rather than creator. In addition the solution is transitional, making relatively minor reductions to GHG emissions while retaining all the other disadvantages of internal combustion engines.

8.2 Drop in biofuels

Advanced biofuels (“second generation”) are produced from non-edible biomass including agricultural and forestry residues. They have low net CO2 emissions and cause zero or low indirect land use change.

The study assumed that the resulting fuel could be used in a conventional diesel locomotive, either directly or with realistic fuel system modifications.

KiwiRail engaged with Air New Zealand, which has a project to advance the production of Sustainable Aviation Fuel, a drop in replacement for aviation kerosene. Drop in diesel fuel is a by-product ofSAF production.

While there are issues, including poor energy return on investment, and competition for a limited supply, second generation drop in biofuel was identified as the next best alternative to the battery and electric option. It also offered the possibility of early decarbonisation of the conventional but new generation diesel-electric fleet being retained to 2040 or beyond, ahead of their scheduled retirement and replacement by battery-electric locomotives.

9. Hybrid internal combustion locomotives

Hybrid locomotives, battery locomotives range extended by onboard diesel generators or diesel-electric locomotives with their efficiency increased by adding batteries, were initially considered to have promise, but quickly rejected when examined more closely.

At the required size of diesel generator for a range extender the fossil fuel equipment quickly displaces significant battery capacity, leading quickly to a situation where as little as 1/3 of the energy used is battery sourced. In effect, adding a diesel power source to a battery locomotive on KiwiRail duty cycles you quickly “chase your tail” and undermine the ability to complete most of a route on battery.

Hybrid consists, though, do have merit. This is where a standard battery-electric locomotive is paired with a conventional diesel locomotive and the two (or more) work in multiple to maximise the use of battery energy and the amount of battery energy recovered. The major OEMs advocate this as a transitional solution and are developing on board software to manage the consist.

Mixed consist operation is recommended as a way to commence pilot operation of battery locomotives before the enroute charging infrastructure is in place, to gain experience in their operation and achieve early reductions in emissions.

10. Conclusions and discussion

Taking technological risks into account the study recommended a balanced approach.

Electrification is recommended for decarbonising most of the KiwiRail mainline locomotives and battery electric is the way of achieving this for the majority of routes. This assumes that battery and charging technology will develop over time.

To minimise the risks around this assumption, parallel pilot battery electric and OLE electrification on selected busy routes was recommended to buy time for confidence to be gained while guaranteeing significant decarbonisation progress.

While only two routes, 46% of the entire KiwiRail freight task will be decarbonised by this initiative, using proven technology able to be delivered to a planned schedule. Most of the modelled growth will occur on these routes, so this proportion will grow to 60%.

Battery electric must be considered a system comprising locomotives, charging and operational changes to best maximise the strengths and minimise weaknesses of the solution. Therefore, introduction must be considered as a transformation programme involving far reaching change to KiwiRail’s organisations, operations, facilities, and people.

It was also recommended that maximum use be made of diesel powered rail now to take advantage of its inherently lower GHG emissions compared to road.

Fuel cell hydrogen performed poorly but its suitability can be revisited in the late 2030’s when the DM fleet is nearing its major midlife overhaul decision and a decade of progress has been made with the hydrogen and battery solutions.