Keeping goods moving between the Islands

New Zealand’s domestic freight system would be unprepared if the ferry terminals were removed. Urgent action should be taken to strengthen the system’s resilience, which could be achieved with two backup linkspans and a barge to facilitate the re-routing of the ferries. Photo: KiwiRail

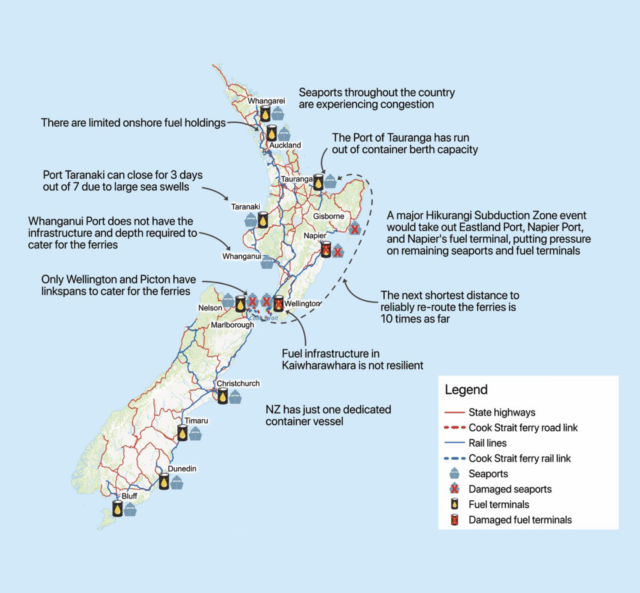

Freight moves very efficiently to ensure that goods are available when and where they are needed. However, a major Hikurangi Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami taking out the Cook Strait ferry terminals for an extended period would bring immediate chaos to the movement of goods between the North and the South Islands. The impact of an 8.9 magnitude Hikurangi Subduction Zone event would be similar to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan. GNS Scientists have reported a one-in-four chance of such an event occurring in the next 50 years. Given the criticality of the Cook Strait ferries in connecting the North and South Islands and their exposure to natural hazards, we conducted research on how a three-month Cook Strait ferry terminal outage would impact the movement of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCGs) and what could be done to address subsequent bottlenecks and keep goods moving. To inform our research, 30 industry experts were interviewed across the freight transport sector, enabling a wide range of perspectives to be captured.

Re-routing the ferries

During an extended Cook Strait ferry terminal outage, and provided the ferries are still operational, the initial response would be to re-route the ferries to alternative seaports. However, Wellington’s CentrePort and Port Marlborough are the only seaports with linkspans connecting the ferries to the land, and the terminals have been purposefully designed to handle rail freight. Furthermore, in the event of a major Hikurangi Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami, Napier Port and Gisborne’s Eastland Port would be taken out. Because of this, re-routing the ferries to alternative seaports is not without its challenges.

The shortest route to operate would be between Port Nelson and Whanganui Port. However, Whanganui Port lacks the infrastructure and depth to accommodate large vessels like the Cook Strait ferries. The alternative would be to use Port Taranaki, but that seaport can close off for three days out of seven when there are large sea swells. Therefore, the subsequent shortest distance to reliably re-route the ferries would be between Port Nelson and the Port of Tauranga, a distance 10 times as far as the usual route. Although possible, this would be incredibly inefficient as the ferries are designed for a quick transfer and have limited carrying capacity.

Moving freight by alternative modes

Given these challenges, it is likely that most FMCGs will be moved by coastal shipping and higher-value or urgent goods by air. Contrary to the ferries, coastal vessels cannot carry curtain-sider trucks or most rail wagons, so goods would have to be loaded into shipping containers, of which there would be shortages since New Zealand runs at a deficit. Moreover, each curtain-sider truck and trailer unit carrying perishable FMCGs would need about two to three 20-foot refrigerated containers. These containers would also require generators to power them, fuel to run the generators, container trucks and drivers. The demand for all these resources would be significant, given that the ferries move mostly non-containerised goods in about 460 trucks and 200 rail wagons daily.

As for the movement of shipping containers, since July 2024, New Zealand has just one dedicated container vessel and, therefore, depends on international shipping lines for domestic container movements. However, the frequency of service of these vessels is limited, and their schedules are unreliable. They make sudden service changes to meet their international commitments, which often take priority. During a Cook Strait ferry terminal outage, these international vessels would unlikely introduce additional services but rather work with the capacity they have already allocated to New Zealand. Fortunately, domestic and international vessels move many empty shipping containers, which, rather than travelling empty, could be loaded with certain freight, such as non-perishables. However, the volume of freight moved by the Cook Strait ferries significantly exceeds the capacity available in the coastal shipping sector.

Critical infrastructure interdependencies

Freight transport is highly reliant on other critical infrastructure, such as fuel and electricity. Adding to the above-mentioned issues, New Zealand has limited onshore fuel holdings, some of which would fail in a major Hikurangi Subduction Zone event. For instance, Wellington’s Kaiwharawhara site, the primary supply for the Cook Strait ferries, is aged and vulnerable and would likely fail. Like Napier Port, the nearby fuel terminal in Napier would be taken out. The absence of these fuel terminals would place further pressure on the remaining sites. Additionally, electricity outages would result in most key service stations and cell towers ceasing operations in the affected areas, as they do not have backup power sources. As a result, demand for generators and fuel would increase even more.

Information availability

The unavailability of information in the wake of a major disaster would create further complexity in the movement of goods between the North and South Islands. Firstly, information such as the status of critical infrastructures and their outage and restoration times is not available in a single location. Secondly, information about capacity (e.g., carrying capacity of vessels and berth/yard capacity at seaports) may not be immediately available. Finally, the systems used in the freight transport sector are mostly not interoperable and sometimes paper-based, which impedes the flow of information and the swift reconfiguration of freight operations in the wake of a disaster.

Policy constraints

Our research shows the critical role of policy in the building of freight resilience. Ultimately, the effective re-routing of the ferries and the use of coastal shipping depend on the availability of berth/yard capacity and on handling performance at seaports. Seaport congestion can result in domestic and international vessels being unable to load and discharge their containers. In the case of the Port of Tauranga, congestion is compounded by an underlying policy constraint. Since 2019, the Port of Tauranga has been waiting for resource consent to increase its berth capacity. The delay has resulted in challenges, such as running out of container berth capacity earlier this year. Another policy constraint relates to the Government’s commitment to moving away from fossil fuels like diesel. At this stage, it is unclear what alternative fuel, or fuels, will be supported going forward, and the infrastructure and resources needed to support such a transition are not there. As such, shipping companies are reluctant to invest in new (alternative fuel) or used (diesel) vessels without guidance about the future of alternative marine fuels. Since vessels are typically in operation for some 30 years, a number of alternative fuels might not be supported in the future and diesel vessels might be financially penalised.

The map below recaps some of the constraints identified in our research.

Key constraints following an extended Cook Strait ferry terminal outage.

Recommendations

As it stands, New Zealand’s domestic freight system would be unprepared if the ferry terminals were taken out. Therefore, we believe action should be urgently taken to strengthen the resilience of New Zealand’s domestic freight system. This can be achieved by acquiring two backup linkspans and a barge to facilitate the re-routing of the ferries. Granting the Port of Tauranga resource consent would increase the berth and handling capacity, a key requirement from a national resilience perspective. A clear policy on future marine fuels would encourage domestic operators to acquire additional vessels, increasing the domestic carrying capacity and, therefore, reducing the dependence on international shipping lines. Lastly, given the exposure of New Zealand seaports along the East Coast to a Hikurangi Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami and the fact that Port Taranaki can close off for days, the proposal of Whanganui Port to accommodate the Cook Strait ferries and other larger vessels in an emergency should be reconsidered.

This research was conducted by Nathan Brutsch under the supervision of Cécile L’Hermitte (University of Waikato), Liam Wotherspoon (University of Auckland) and Richard Mowll (Wellington Region Emergency Management Office). It was funded by Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE (the New Zealand Centre for Earthquake Resilience) and supported by the University of Waikato.